The IRS Collection Financial Standards are the yardstick the IRS uses to decide what you can reasonably afford to pay toward back taxes. They’re for federal tax administration—not bankruptcy—and the current set took effect April 21, 2025. If you’re looking for bankruptcy figures, those live with the U.S. Trustee Program and differ in structure and amounts. IRSDepartment of Justice

In 2025, the IRS also tweaked its inflation methodology for these standards, basing them on the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) index rather than CPI—a shift intended to better reflect actual consumption. That change shapes the numbers you’ll see in the PDFs for 2025. IRS

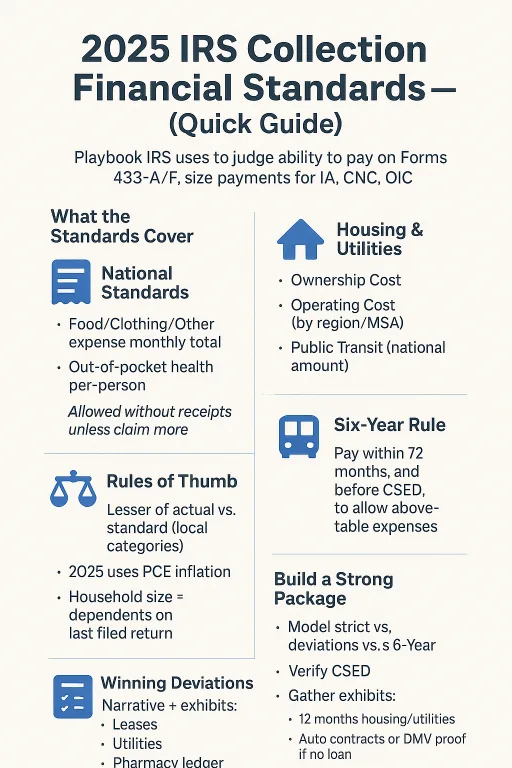

What the Standards are—and how the IRS really uses them

At their core, the standards implement the IRS’s “necessary expense” test: expenses must be needed for your (and your family’s) health and welfare and/or the production of income. They’re also the backbone of financial analysis on Form 433-A / 433-F, installment agreements, currently not collectible (CNC) decisions, and offers in compromise (OIC). IRS

The system breaks down into:

- National Standards (fixed nationwide) for:

- Food

- Housekeeping supplies

- Apparel & services

- Personal care products & services

- Miscellaneous

- National Standards (per person) for out-of-pocket health care

- Local Standards (county/MSA-based) for housing & utilities and for transportation (with a nationwide ownership allowance and regional/MSA operating costs). IRS+3IRS+3IRS+3

CPA pitfall: Treating the standards as “caps” across the board. National categories work differently from Local ones. Under the national standards for food/clothing/other items, the IRS allows the full national total for your household size without questioning actual spend (unless you’re claiming more). By contrast, Local standards typically allow the lesser of your actual expense or the local standard. Mixing those rules leads to avoidable denials. IRSTaxpayer Advocate Service

CPA opportunity: When a client’s actuals legitimately exceed a standard and the family would otherwise be left short (think necessary medical care, unique commuting needs, or unavoidable housing costs), you can argue a deviation with documentation. The IRS explicitly allows deviations when the standards would be inadequate for basic living. I’ve won many of these—paper wins policy. IRS

National Standards: Food, Clothing & Other Items

These five categories roll up into a single monthly total based on household size. For 2025, the totals are (examples): $839 for one person; $1,481 for two; $1,753 for three; $2,129 for four; +$394 for each person over four. (These figures change periodically—always check the PDFs linked below.) IRS+1

How allowance works in practice

- You’re allowed the national total for your household size without substantiation.

- If you claim more than the total, you must substantiate the excess in the categories that exceed it.

- Miscellaneous is part of the total and cannot be separately deviated; it’s there to absorb small, otherwise uncategorized necessities. IRS+1

CPA pitfall: Households with non-dependents (roommates, adult children not claimed on the return) often miscount the “household size” for national standards. The IRS generally looks to your most recent tax return dependent count—get ready to justify any difference (e.g., a newborn, elder moved in). IRS

CPA opportunity: When spending is below the national total, the IRS doesn’t reduce the allowance; you still get the full national total. That can preserve cash flow for other necessary but under-recognized costs (e.g., pending dental work, car registration spikes). Taxpayer Advocate Service

National Standards: Out-of-Pocket Health Care

For 2025, the national per-person allowances are $84 (under 65) and $149 (65+). These apply in addition to your health insurance premiums. IRS

What’s included: co-pays, prescriptions, over-the-counter meds, glasses/contacts, medically necessary supplies. Electives (cosmetic procedures, whitening, etc.) are generally excluded. IRS

CPA pitfall: The per-person standard is low for clients with chronic conditions. If your actuals are higher and necessary, pursue a documented deviation (invoices, treatment plans, pharmacy ledgers). I frequently attach a short physician letter connecting the spend to health/welfare—simple and effective.

CPA opportunity: Timing matters. If you’re planning a payment arrangement and know certain treatments/prescriptions are imminent, front-load your documentation so your financial analysis reflects reality, not last quarter’s lighter spend.

Local Standards: Housing & Utilities

The IRS publishes county-level tables (and a Puerto Rico table) with five family-size columns. Included: mortgage or rent, property taxes, insurance, maintenance/repairs, gas/electric/water, garbage, landline, cell phone, cable, and internet. IRS

Key rule: The IRS generally allows the lesser of your actual housing & utilities or the local standard for your county and family size. If your lease or mortgage is above the local standard, you’ll need a deviation argument anchored in basic living needs (e.g., medically necessary proximity to care, lack of cheaper comparable housing, fixed-term lease with early-termination penalties). Taxpayer Advocate Service

CPA pitfall: HOA dues and special assessments get missed or mislabeled. They are part of housing costs—just document them clearly in the housing bucket. Also, clients often forget required renters’ insurance—include it.

CPA opportunity: Utility volatility (seasonal spikes, arrears payment plans) supports deviations. I attach 12 months of utility statements and a worksheet showing averages and spikes. If you’re on an arrears plan with the utility, attach the plan agreement.

Local Standards: Transportation

Transportation is split into:

- Ownership costs (nationwide)—maximum monthly allowance for car loan/lease payments (up to two vehicles if justified; typically one for a single taxpayer).

- Operating costs (regional/MSA)—fuel, maintenance, insurance, registration, parking, tolls.

- Public transportation (nationwide)—a per-household allowance.

For 2025, examples include $662 ownership for one car ($1,324 for two), and $244 for public transit; operating costs vary by region and by one vs. two cars (e.g., Northeast region $302 for one car; $604 for two—MSA adjustments apply). If you have a car payment, your allowable transportation is ownership + operating; if you don’t, you only get operating. IRS

CPA pitfall: Clients with paid-off cars often expect an “ownership” allowance—that allowance exists only if you have a loan/lease. Plan around this when modeling cash flow.

CPA opportunity: It’s possible to allow both a car and public transit if needed for health/welfare or income production, limited to the lesser of actual vs. standards. This is underused for families juggling school, shift work, and medical visits. IRS

The “Six-Year Rule” (and why we model it early)

If you can’t full-pay and don’t qualify for a simple payment plan, the IRS may still allow expenses that exceed the standards and certain other expenses (e.g., minimums on student loans or credit cards) so long as your entire liability (tax, penalties, interest) is fully paid within six years (or before the CSED, if sooner). This window was extended from five to six years in 2012 and remains pivotal to planning. IRS

CPA pitfall: We routinely see payment proposals that ignore CSED (Collection Statute Expiration Date). If your CSED arrives before six years, the proposal must fully pay by CSED, not by Year Six. Misalignment here kills otherwise viable deals.

CPA opportunity: If a client is close to six-year feasibility, consider short-term belt-tightening plus documented deviations (e.g., medical, mandatory commuting costs) to thread the needle. Where six years is unrealistic, pivot to CNC or OIC strategy before wasting months. (IRM 5.8.5’s financial-analysis framework cross-references these judgments; the 433A/OIC math must reflect reality, including asset equity.) IRS

Documentation strategy that wins (what I attach and why)

- Twelve months of housing and utilities with a summary worksheet—shows true averages and seasonal spikes.

- Insurance declarations (auto, renters/home, health)—clear coverage and costs.

- Autos: loan/lease contracts, payment histories, and DMV registrations; if no payment, make the ownership vs. operating rule explicit to manage expectations.

- Medical: pharmacy ledgers, EOBs, recurring co-pay logs, physician letter tying expenses to necessity.

- Public transit: monthly pass invoices; if combined with car use, explain the work/health split.

- Any deviations: a short narrative with exhibits. The standards aren’t a brick wall; they’re a starting point—deviations live or die on paper.

CPA pitfall: Submitting an immaculate Form 433 but no exhibits. The IRS can’t “just trust” you on deviations—no docs, no deviation.

Common traps I see every week (and how to avoid them)

- Counting the wrong household size. If your return doesn’t reflect current reality (newborn, elder care, divorce), explain and document the difference (birth certificate, lease addendum, caregiver contract). IRS

- Ignoring shared expenses. Roommates and partners not claimed as dependents complicate allocation—don’t overstate your share, and show the math.

- Luxury car leases. If ownership is way above standard, the IRS may push you to downsize; structure proposals around the operating allowance and a transition plan. IRS

- Under-documented medical deviations. Good people with real conditions get denied because the file is thin. One doctor letter + a ledger often flips the decision. IRS

- Over-relying on national totals. Remember: Local housing/transport are lesser-of rules—your higher actuals won’t automatically carry. Taxpayer Advocate Service

- Treating standards like permanent truths. They change. If you printed the PDFs, re-check them before you negotiate or submit. IRS

How the Standards tie into IA, CNC, and OIC (and when to choose what)

- Streamlined Installment Agreements (IAs) often skip full financials when you’re under certain thresholds. If you’re above or need a lower payment, the standards drive what’s “affordable.” IRS

- Currently Not Collectible (CNC): If using the standards (with deviations) still leaves you unable to meet basic living expenses, CNC is in play—your file has to prove the hardship. Pro Bono Desk Manual

- Offers in Compromise (OIC): The standards feed the reasonable collection potential (RCP)—monthly disposable income (MDI) × a multiplier plus net equity in assets. This is where modeling ownership vs. operating, public transit, medical deviations, and household size can swing outcomes by five to six figures. IRS

CPA opportunity: Before committing to OIC, we run side-by-side models:

(A) strict standards; (B) standards + targeted deviations; (C) six-year feasibility; (D) CNC baseline. The winner is usually obvious once the paperwork is solid.

Worked example (condensed)

Facts: Single filer in Miami-Dade, FL with a 2019–2023 balance, steady W-2 income, paid-off Corolla, 20-mile commute, insulin-dependent diabetes, renting a 1-bedroom.

- Food/Clothing/Other: We claim the national total for one person (2025 value per PDF) and don’t submit receipts (unnecessary unless we go over). IRS

- Health care: The $84 national out-of-pocket allowance is clearly insufficient (monthly prescriptions/supplies > $250). We attach pharmacy ledger + endocrinologist letter and seek a deviation to actuals. IRS

- Housing & utilities: We gather lease, 12 months utilities, renters’ insurance; Miami often sits near or above local standards. If a renewal spiked rent beyond the local table, we document market comparables and any penalty to break the lease and argue a temporary deviation until renewal. IRS

- Transportation: With no loan, we get operating only (South region table) and no ownership allowance. For occasional Metrorail use tied to medical appointments downtown, we include transit passes and explain dual necessity (permitted if needed). IRS+1

- Outcome: The deviation on medical plus a near-standard housing figure gets us to a manageable MDI. We test six-year feasibility versus CSEDs; if full pay before CSED is viable, we propose a tailored IA; if not, we pivot to OIC with strong exhibits.

Evidence and policy notes (for fellow pros and the curious)

- The IRS’s financial-analysis rules and the “lesser of actual vs. standard” principle for local categories are laid out in the IRM 5.15.1 (Financial Analysis Handbook) and discussed by TAS research. Good reminders when an RO or ACS employee applies the rules inconsistently. IRSTaxpayer Advocate Service

- Policy baselines and April 21, 2025 effective date live on the IRS standards pages themselves. Always cite the page and attach the current PDFs in your submission. IRS

- The IRS confirmed the 2025 PCE inflation basis on the standards landing page. Useful to explain year-over-year deltas to skeptical clients (or reviewers). IRS

Download the 2025 Standards (PDF)

- National Standards – Food, Clothing & Other Items (PDF): https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-sbse/national-standards.pdf IRS

- National Standards – Out-of-Pocket Health Care (PDF): https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-sbse/out-of-pocket-health-care.pdf IRS

- Local Standards – Transportation (PDF): https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-sbse/transportation-standards.pdf IRS

- Local Standards – Housing & Utilities (PDF): https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-sbse/all-states-housing-standards.pdf IRS

(Note: PDFs are hefty—housing runs ~129 pages. If you print, re-check these links before filing to make sure you’ve got the current version.) IRS

Final take (from the chair on my side of the table)

These standards aren’t there to punish you; they’re there to standardize judgments—and allow flexibility when the basic-needs story is properly told. The difference between a payment you can live with and one that collapses in month three is almost always documentation + narrative:

- Model with the correct rules (national vs. local behavior).

- Document any deviation with specificity.

- Check CSED and sanity-check six-year math before choosing IA vs. OIC vs. CNC.

- Package your Form 433 with exhibits that speak for you.

If you want a seasoned eye on your numbers—or a ready-to-submit 433 package with the right exhibits—I can help. Start by organizing your facts in my AI Tax Chat and we’ll take it from there.

Frequently Asked Questions about IRS Collection Financial Standards

Understanding the Financial Standards Framework

They’re the benchmark the IRS uses to evaluate your ability to pay when you owe back taxes. Expenses that satisfy the “necessary expense” test—needed for health and welfare or to produce income—are allowed and flow directly into financial analyses for Form 433‑A/433‑F, Installment Agreements (IA), Currently Not Collectible (CNC), and Offers in Compromise (OIC). The current set is effective April 21, 2025. In practice, think of the tables as a starting point: when they leave a household short, you support a documented deviation (with proof) so the file reflects real basic‑needs spending.

Reference: IRS Collection Financial Standards

National Standards combine five categories into a single monthly total by household size (food, housekeeping supplies, apparel & services, personal care, miscellaneous). You’re allowed the total without questioning what you actually spent—unless you claim more than the total. If you must exceed the total due to special circumstances, substantiate the excess (receipts, statements, short narrative). A common mistake is treating this total as a hard cap and demanding receipts even when you’re not exceeding it.

Reference: National Standards – Food, Clothing and Other Items

PDF Table: National Standards PDF

For 2025, the minimum monthly out‑of‑pocket allowance is $84 per person (under 65) and $149 (65+). This amount is allowed in addition to health‑insurance premiums. It covers routine co‑pays, prescriptions, glasses/contacts, and medically necessary supplies. If your necessary costs are materially higher (e.g., insulin and supplies), build a deviation packet: pharmacy ledger, receipts/EOBs, and a brief physician letter tying the costs to health/welfare.

Reference: National Standards – Out-of-Pocket Health Care

PDF Table: Out-of-Pocket Health Care PDF

Housing & Utilities include rent/mortgage, property taxes, insurance, maintenance/repairs, gas/electric/water, garbage, landline, cell, cable, and internet. Generally, you’re allowed the lesser of (a) your verified actual expense or (b) your county’s local standard for your family size. If you’re locked into a lease above the standard, you can argue a (usually temporary) deviation with documentation—lease terms, market comps, and reasons cheaper comparable housing isn’t feasible.

Reference: Local Standards – Housing and Utilities

PDF Table: All States Housing Standards PDF (129 pages)

Transportation has three parts: (1) ownership (loan/lease payment allowance; up to two cars if justified), (2) operating (fuel, insurance, maintenance, etc.) set by region and sometimes MSA, and (3) public transit (national figure). For 2025, ownership is $662 for one car ($1,324 for two) and public transit is $244; operating costs vary by region/MSA. If your car is paid off, you don’t receive the ownership allowance—only the operating allowance. You can allow both car and transit if both are needed for health/welfare or income production, subject to lesser‑of rules.

Reference: Local Standards – Transportation

PDF Table: Transportation Standards PDF

The IRS generally aligns the number of persons allowed for necessary living expenses with the dependents on your most recent tax return. If your household changed (newborn, elder moved in), explain and document it (birth certificate, school/medical records, lease addendum). Clearing this up early prevents pushback and helps deviations stick.

Reference: IRS Collection Financial Standards

Yes. If the facts show the tables would be inadequate for basic living, the IRS may allow actual expenses. You need documentation plus a short narrative tying each excess to health/welfare or income production. The Internal Revenue Manual instructs employees to verify and analyze financials to determine ability to pay; strong exhibits often tip the decision.

Reference: IRS Collection Financial Standards

IRM Reference: IRM 5.15.1 Financial Analysis Handbook

Advanced Standards Applications

If you can’t full‑pay now and don’t qualify for a simple plan, you may qualify for the Six‑Year Rule: the IRS can allow expenses exceeding the Standards (and certain other minimum payments) so long as the entire liability—tax, penalties, interest—is fully paid within six years (or before CSED, if sooner). Use it when strict tables leave you too tight but realistic cash flow can retire the debt in ~72 months. Always model against CSED.

Reference: IRS Collection Financial Standards

No. The Collection Financial Standards are for federal tax administration only. Bankruptcy uses separate figures under the U.S. Trustee Program. Don’t mix the two—courts and trustees won’t accept IRS collection tables in that context.

Reference: IRS Collection Financial Standards

U.S. Trustee Program: Means Testing Information

The IRS updates the amounts periodically and posts downloadable PDFs. The current set is effective April 21, 2025. If you print the tables, re‑check the site before filing or negotiating to ensure you have the latest numbers. When I submit a 433 package, I attach the relevant PDF page(s) to anchor the figures to the current publication.

Reference: IRS Collection Financial Standards

Key PDFs: National Standards | Health Care | Housing | Transportation

For 2025, the IRS notes that the inflation metric used to calculate the collection financial standards is the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) index (rather than CPI used prior to 2024). PCE can shift the dollar amounts because it better reflects consumer behavior and is the inflation measure monitored by the Federal Reserve. If your allowance looks “off” relative to last year, this methodological change may be the reason.

Reference: IRS Collection Financial Standards

The Standards drive ability‑to‑pay math on Form 433‑A/F. For IAs, they frame what’s “affordable”; for CNC, they help document that—even with the Standards (and any deviations)—you can’t meet basic living costs; for OIC, they feed Monthly Disposable Income used to compute Reasonable Collection Potential (RCP) alongside asset equity and remaining statute time. The IRM directs analysts to apply Standards/allowances and compute capacity over the remaining CSED.

IRM References: IRM 5.15.1 Financial Analysis Handbook | IRM 5.8.5 Financial Analysis (OIC)

The IRS generally has 10 years from assessment to collect (the Collection Statute Expiration Date, or CSED). Certain events suspend or extend that clock, pushing out the end date by the suspension period. Any plan must still fully pay by CSED (or use another resolution, like OIC/CNC) to make sense. Always model proposals with the CSED timeline up front.

Reference: Time IRS Can Collect Tax

TAS Backgrounder: Collection Statute Expiration Date (CSED)

Practical Implementation Tips

No loan or lease means no ownership allowance—you still receive the operating allowance for your region/MSA. You can claim both car and public transit when both are necessary for health/welfare or income production, but your combined allowance is still limited by the lesser‑of rules (actual vs. standards). Document the use‑case (e.g., shift work plus medical appointments) and include passes/receipts.

Reference: Local Standards – Transportation

Transportation PDF: Transportation Standards PDF

Yes—cell phone service, cable, and internet are expressly listed within Housing & Utilities for the primary residence. Submit full monthly statements (not just bank debits) so the IRS can see service type and service address. Where bills fluctuate seasonally, add a 12‑month average worksheet; it prevents cherry‑picking a light month that later causes a default.

Reference: Local Standards – Housing and Utilities

Use the IRS PDFs and highlight the page(s) that apply to your county/family size/MSA. Printing the exact page and including it with your Form 433 exhibits minimizes disputes later.

Direct links: National Standards PDF | Health Care PDF | Housing PDF | Transportation PDF

Build a deviation packet: (1) a short narrative tying costs to health/welfare, (2) pharmacy ledgers and/or EOBs, (3) a brief physician letter confirming ongoing necessity, and (4) 12 months of receipts where possible. Reference the IRS allowance table, then explain why applying it as‑is leaves the household unable to meet basic needs. The IRM supports allowing actuals when the Standards are inadequate.

Reference: National Standards – Out-of-Pocket Health Care

IRM Reference: IRM 5.15.1 Financial Analysis Handbook

Under the Six‑Year framework, you provide financial information but don’t have to substantiate every reasonable expense the way you would in a strict deviation case. Guardrails remain: full pay in six years and within CSED, and you must stay current. I still attach core exhibits because better documentation improves acceptance and prevents downstream disputes.

Reference: IRS Collection Financial Standards

Four big ones: (1) household size not tied to the last return (no explanation/documentation), (2) claiming ownership with no loan/lease, (3) missing source docs for deviations (e.g., rent above local standard with no comps or lease terms), and (4) ignoring CSED math, which can doom a Six‑Year plan that looks fine on paper. Fix those early—they’re all preventable with exhibits and a short narrative.

References: Standards Overview | Transportation Rules | CSED Basics

Use the current PDFs, calculate allowances correctly (national vs. local behavior), and attach a clean exhibit set: 12 months of housing and utilities, insurance declarations, auto loan/lease or DMV proof (if no loan), transit passes, and medical documentation. If you’re near feasibility, model three ways—strict standards, targeted deviations, and Six‑Year—and check CSED before choosing IA vs. CNC vs. OIC. This mirrors how the IRM instructs employees to analyze financials and ability to pay.

Primary References: Standards Overview | IRM 5.15.1 Financial Analysis Handbook | IRM 5.8.5 Financial Analysis (OIC)